Overview

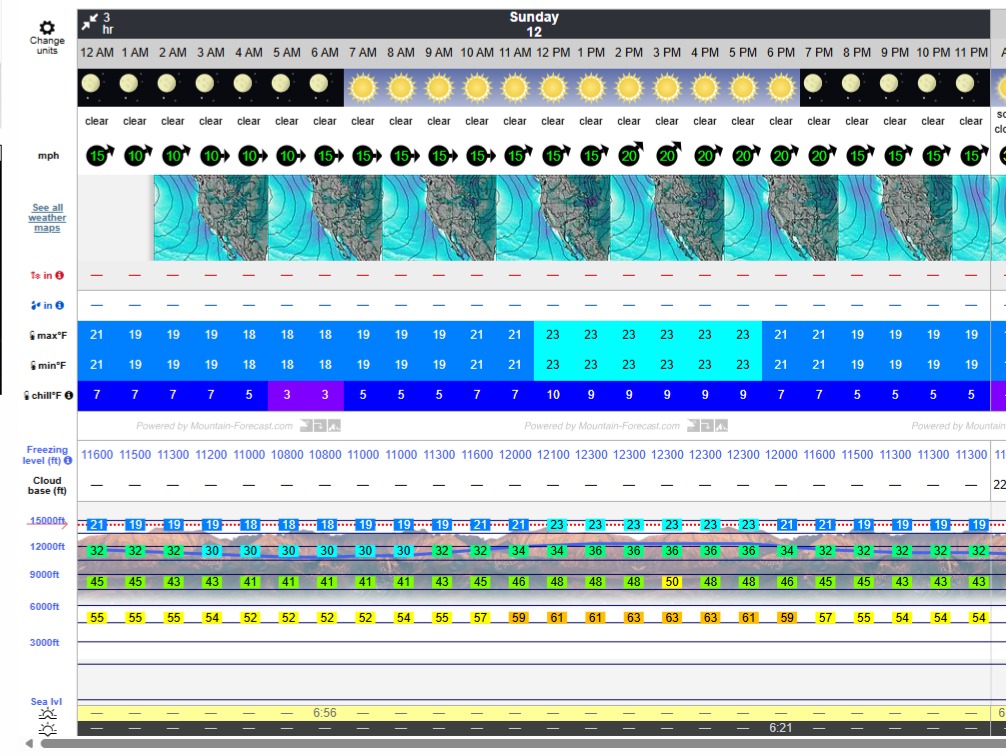

Going off-trail and getting to the top of any one of Glacier Park’s many peaks can be one of the most memorable things you’ll ever do. And it’s becoming increasingly popular. Surprisingly the vast majority of peaks in the park can be reached without any technical gear. We refer to this as “scrambling” or “peak-bagging.” It can also be called “climbing” as it often involves strategic route finding, steep cliffs and ledges, dangerous exposure, 3,000′ to 6,000′ feet elevation gain, and a lot of careful placement of hands and feet on loose rock.

Off-trail travel and climbing is allowed in Glacier National Park with few exceptions. Climbing and exploring are considered historical and cultural activities which are protected by law, and while the NPS allows it they certainly do not promote or encourage it (because it’s dangerous and people don’t always come prepared). There are sensitive environments where off-trail travel is strictly prohibited. An example of this is all areas off the boardwalk in the Logan Pass area (except designated climber trails for Reynolds and Oberlin). There may be occasional temporary closures due to wildlife, rescues, resource protection, or other hazards.

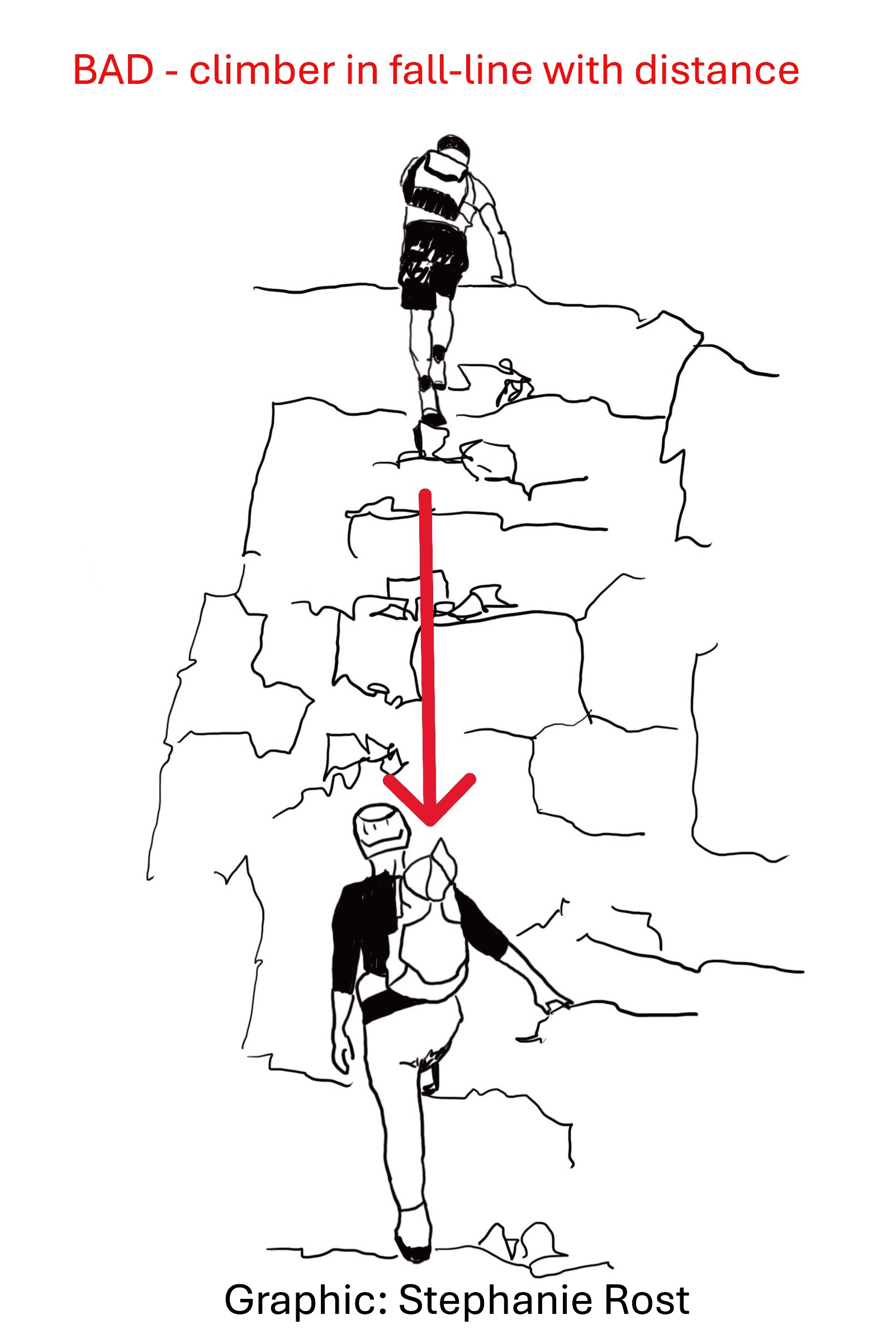

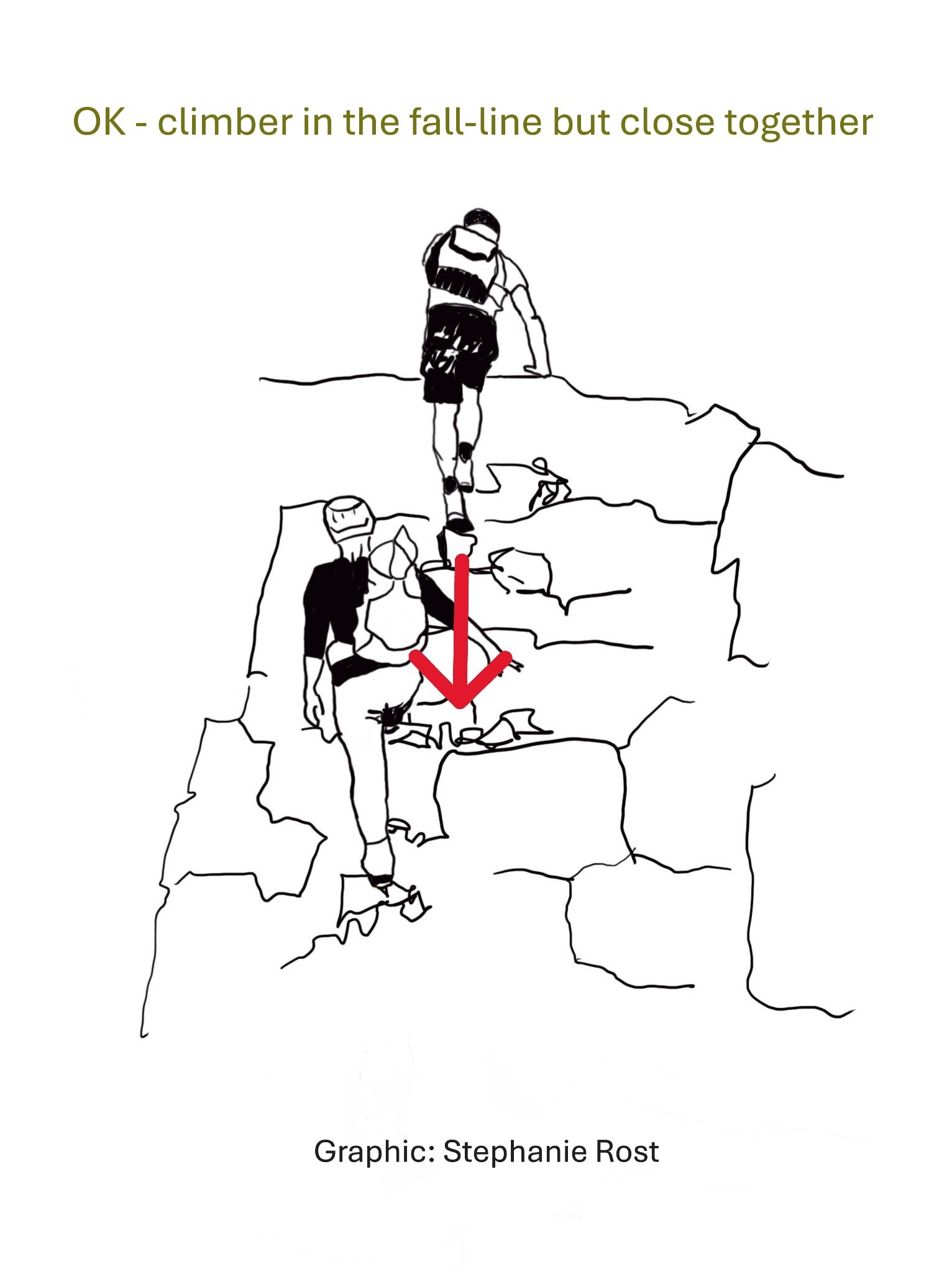

There are 234 named peaks or high points as accepted by the Glacier Mountaineering Society. They’re a great organization if you are looking for a way to join others on a climb or learn more about climbing. Though a summit of most peaks doesn’t require ropes, it must be noted this activity is inherently dangerous. In fact it can be, and has been, DEADLY. One missed step, a slide on a wet rock, or a loose rock pulling out can lead to disaster. Anyone engaging in these types of activities should recognize, and never underestimate, the potential danger involved.

With the risk disclaimer out of the way, now it’s time to talk turkey. I love climbing in Glacier. It’s without question my favorite thing to do. I’ve climbed nearly 200 peaks in the park with about 125 of those being unique (several others were repeated). I enjoy taking experienced climbers with me but I also choose to prioritize taking “newbies.” I think it’s important for those getting started as peak-baggers to find someone with experience to mentor them. This simply helps make climbers safer.

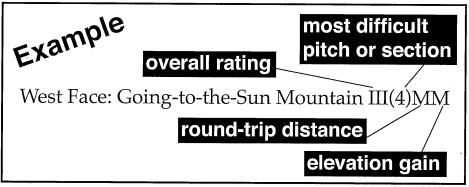

First and foremost I encourage climbers to be prepared. This necessitates an understanding of weather, wildlife, rock conditions, route planning, personal fitness, group dynamics, and the ability to mitigate, retreat, self-rescue, or spend the night. So, what resources are available to help one learn how to climb safely in the park? The two best print sources of this information are A Climber’s Guide to Glacier National Park, by J Gordon Edwards, and the Climb Glacier National Park series by Blake Passmore. These references are loaded with history, geography, geology, route info, and tips on climbing techniques.

People often get route information, often referred to as “beta” from online sources. Two of the most common online sites for beta are mountainproject.com and summitpost.org

And now my two cents-worth about climbing ethics: Please, be a Conservator and not a Consumer. Follow Leave No Trace Ethics. Respect our Wild Places and our Public Lands. Model good stewardship. Follow GNP rules.

Ethics Examples:

- Pack out your trash, including TP. Bury your poop in a cat hole

- Don’t build cairns unless absolutely necessary for navigation

- Don’t trample vegetation/flowers

- Keep an appropriate distance from wildlife

- Don’t carve your name on rocks or trees

- Don’t disturb tribal artifacts or archeological sites

- Get a permit if it’s required

The next few parts will have content to help you be a safe and successful climber. This is not a guide book, nor is it to be considered an exhaustive manual of everything you need. It’s just me, imparting some experience, to share the joy of climbing in Glacier National Park. Please continue on to read part 2.

Helmets are COOL!